David Cassidy is a really nice Pop Star, Teen Idol, Guy, Bloke, Sex Object, Person

By Giovanni Dadomo,

Sounds Magazine

3 April 1976

By our Wop on the spot, Giovanni Dadomo

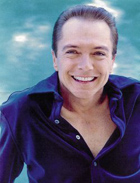

THE SKIN is brown and clear, stretched taut across the cheekbones. He is Yes, much thinner than of yore. And yes, boyishly good looking.

The eyes though, are red. It's almost as if the eyes belonged to someone else, some alien, raw and red as a carrot, snuck into this taut sun-kissed epidermis the handful of little girls parked outside the hotel entrance these two nights now know and love.

David Cassidy's a lot smaller than I expected. Just woken up, those eyes, so very terribly raw, give an immediate impression/parallel of Dorian Gray, or the Paul Williams Character, Swan, in the excellent Phantom Of The Paradise. Perhaps in one of the trunks there's a Fabulous 208 poster with the real Cassidy visage lined, pimpled and mounted with a few silver hairs perhaps not.

As a matter of fact I've always had a soft spot for the kid, always had the impression brought back to me by the tired eyes in the fresh face that he was trapped inside a contract-controlled teenage Frankenstein monster.

I had accordingly anticipated the eventual breakdown of aforementioned artifice I was nonetheless delighted when the 'real' DC started upsetting teen reporters by confessing he was a doper, gay, and/or inviting them to play in blue movies with him.

And it does take guts to fart in the face of success the way Cassidy did considering how he could probably have gone on playing Boy Wonder for another 20 years or so (consider the Osbros, their sights already set on the ultimately-to-be-vacated shoes of such all-purpose media 'good guys' as Bob Hope, Fred Astaire, and John Wayne).

SO IT'S NO real surprise to me that we, as far as it's possible within the confines of a time-limit dialogue, hit it off. Not, I hasten to add, that I'm a big fan of Cassidy's music; even in its later more 'real' stages I still find it a little out of my stamping area (although the first time I heard the Eagles' 'Best Of My Love' I thought it was Cassidy's new single, and am constantly outraging Eagle fans by drawing what I think is not a totally unverifiable parallel).

Anyhow, we have a good 40 minutes of chat (the last 10 minutes of which are granted by DC, who keeps the man from the Sun waiting so we don't break off in mid-sentence), and I quit the hotel feeling pleasant.

(It's only later that I wonder if it's not this ability to make people feel pleasant in his presence that's the real secret of Cassidy's success the next night he appears on Russell Harty and makes its obscene presenter feel just as pleasant. I was disappointed that DC, the liberated DC, didn't react a trifle more abrasively towards Harty's patronising number.)

Now say you were in my place and you'd gone to speak to this guy whose music you didn't particularly care for but whose ability to turn his victim status in the rock 'n' roll scheme of things to his advantage was your major point of interest just what the hell would you talk about?

S'easy you skip the obvious shit questions hurled pell mell in his direction in the hope that one out of the plethora will come up with a spiky quote on its double-edged hook chances are you'll just catch your own bullshit thrown back in your tape recorder. After all, the kid is sharp, no doubt about it.

Instead you mooch around, kicking off with the token opener presented by the lad's helpful Press Office earlier on, to wit the fact that DC is considering making a movie. Izzat true, DC?

"Well, I've read a real fine screenplay, but I'm not really sure I'm going to be doing it." He has, he says, received a whole bundle of screenplays everything from the obvious vehicles for his old blue-eyed, white-toothed Partridge Family persona to its obvious antithesis, ie hard core pornography.

The latter prospect was obviously out, but it's an amusing concept and its would be producer ought to be congratulated on his uncanny sense of humour after all, who could resist the prospect of, say, seeing Donny Osmond roll a couple of numbers, down a quart of red-eye and go down on Linda Lovelace?

But no, DC's not too keen on blue movies right now it's not a nostalgia thing. But it does carry a lot of social significance in the sense of what was going on around that time. "Around that time that James Dean came out... there was a social revolution going on in that young people believed in themselves for the first time they didn't have to go to church and all that shit if they didn't want it..."

I point out that the Dean/teen revolution area has been pretty well covered by a magnificent American movie name of Badlands of a couple of years ago. Cassidy never heard of it; he will, he says, check it out. "But," he says, closing the subject of cinema, 'There's no real movies any more, there are no big studios building up movie stars like in the old days after Dean it pretty much switched to rock 'n' roll stars. Anyway I'm not sure if a movie would be right for me at the moment, I'm attracted to it but I'm not sure I wanna get into that situation where... I'm in a difficult position creatively in that my first priority is to be recognised as a musician."

WE RAMBLE a bit, taking in passing the fact that Cassidy's major heroes in his mid-60's adolescence weren't celluloid ones anyway rather it was the Beatles, Beach Boys and Lovin' Spoonful who were the people he rooted for. "I was 13 the first time the Beatles came over and that led to a whole musical and social revolution so I suppose those people were the biggest influences on me."

Which brings us in tangentially on one Brian Wilson, with whom Cassidy is on pretty good terms. And, being as fascinated as anyone I know by the whole Wilson mystique I can't resist the opportunity of forcing Cassidy into a backseat role, bringing Wilson to the front. Cassidy, to his credit, readily takes up the role of cub reporter thereby assigned him.

"I see Brian quite a lot. He's a very unusual guy a very sweet, very unusual guy..."

And is Wilson writing now, I enquire, all ears...

"He is. As a matter of fact I just wrote a song with Brian and Gerry Beckly. His problem is that he doesn't finish songs.

"No," Cassidy smiles, "he's not brain damaged. There's always exaggeration about someone with Brian's...genius. And I don't use that word lightly he's one of the few people... he can sit down at the piano and write one hook after another. It's just a, constant flow of music with him; all he hears is music. He's a bit eccentric he giggles a lot, laughs a lot. He's like a child but what I like about him is that he's so real, so sensitive. I think of myself as a lot like a child sometimes but Brian... he's living it. But he's given the world an awful lot. I don't think it would really matter if he ever wrote another song."

Would be nice though, don't you think?

"See, his problem is that everybody keeps telling him he's a genius.

" And that's the worst thing you can do to him, to say 'You're a genius, you're the most wonderful writer that ever lived.'

"There's a story that Paul and Linda McCartney went over to see him and they said, 'Brian, 'God Only Knows' is the best rock 'n' roll song' because what can he write? If that's the greatest song, he can never top that, right? And that's the way I think he feels. Because now, when he does something, they're gonna rubbish it if it isn't as great as 'God Only Knows' or 'Good Vibrations' or 'Heroes And Villains' or 'Fun, Fun, Fun', or whatever it was there were a million of 'em.

"BUT HE REALLY is constantly making music and just to be around him is an inspiration. I'm not real close to him I've been over to his house and I've been out with him and I like him a lot. And it really bothers me to hear people rubbish him and hearing bizarre things about him from other people.

"I don't think he's tragic either we all have our neuroses to deal with and maybe people see the way he deals with his and it's tragic, but I don't think he's tragic at all. He lives a very bizarre existence but..."

As long as he's happy.

"Well, I don't know if he's happy I've seen him very happy and I've seen him very sad, but he's alright."

Mr. Wilson it turns out, is no weirder in his own way than Van Dyke Parks, up and coming cult figure and another mutual acquaintance: "He's a real far out guy. Again, very creative, real interesting, and I get on really well with him."

Okay, having diverted the pliant Mr. Cassidy from the intended point of this tκte a tκte, i.e. his second 'new face' album, the recently issued Home Is Where The Heart Is, it's only fair to allow him a few words on the subject.

He is very pleased with it with the musicians, particularly guitarist Steve Ross, whom Cassidy thinks is pretty close to Clapton when it comes to axe-strangling.

"I sat down after it was finished and listened to it and I really liked it, it was a real step towards what I want to do. It's developed in the sense that we really sound like a band, and that's real important. And it's evolving and the guys I worked with are friends of mine, whereas before it was tour, stop, cut an album, tour again. And also it's all me I produced it with Bruce Johnston. Plus the reviews have been really fair and that's real gratifying..."

Cassidy explains that all he wants is to be given a fair hearing it is important then that his music reaches his contemporaries? (He's 25).

"Well, it's a media experience, right? It's a media experience and it's important to me to reach everybody. The music is no more valid if the nine-year-olds like it, or if the 90-year-olds like it, because a 90-year-old or a 25-year-old has got no more right to say what's good or bad than a nine-year-old. It's all subjective experience, and the fact that a lot of 26-year-olds might hear the record and say 'Oh, he's alright after all', that doesn't in itself make the music any better."

The last thing he wanted when he quit the big bucks of the teen circuit, says Cassidy, "was to move from one kind of classification into another.

"I'm real pleased that I'm not making these disco records, 'cause to me that's where music's really stagnating.

"Of course, sooner or later someone'll come along and say disco music's all right because it's been happening all along, since the Four Tops, or since 'Riot In Cell Block Number Nine', or since R&B started since Fats Domino.

"And I'd much rather sit down and listen to Fats Domino doing it. Or listen to Boz Scaggs' new album, which has a lot of that stuff on it but I'd rather listen to that than, say, the O'Jays, because it's different; it's moving, it's growing.

"I think the problem with all those R&B formula records is they're just feels, there aren't really any songs there. And I like feels but I like a regular tune too.

"It's like some of the things that are coming out of Jamaica I could see myself doing reggae music, and I have done it, 'cause it's got a good feel to it, but not if the melody isn't good too."

Amusingly enough the only cut on Cassidy's new album that I'd enjoyed on the one hearing I'd been able to give the platter was a number called 'Goodbye Blues', itself a very soulful, disco if you like, tune.

"It's an old song but it's never been done before. The cat who wrote it wrote 'Son Of A Preacher Man' and a whole lot of things. It's kinda hard to distinguish whether his stuff's country or blues and I like that particular cut a lot. I like what I did with it and the feel we got on it. It was very spontaneous but the whole album was very spontaneous really.

"There's very little over-dubbing because you lose that certain magic... the best records I've heard, most of 'em were cut in mono or on two or maybe four tracks. And you give people 24 tracks and they get a little lost. I had 24 on the album but I didn't use them all I really was aiming for the live sound 'cause I love the pulse of it."

Now that Cassidy has achieved in his own mind at least the sound and feel of a band in the studio, you'd expect the next stop to be some roadwork, right?

It's probably the only time in the conversation that David Cassidy pauses before replying: "It might be a mistake for me to do that right now I want to give the music a chance and give people a chance to digest it and give it a chance to develop.

"But I feel that I've got a direction and it's happening I feel real good about that."

Finally the man from the Sun a ginger-haired marriage of Adolf Hitler and Oliver Hardy arrives for his lunch appointment. Cassidy doesn't want to eat, sidesteps the implications of the RCA house mother (actually quite a burly male) and lights another link in the chain of Marlboro's he's threaded the interview with.

"Y'know" he says, "I gave up smoking about six years ago and I just started again. I really like it."

There are three weeping girls in the corridor outside, being gently but firmly persuaded into the lift.